One of the Things That August Escoffier Did to Back Up His Claim That High Cuisine Is a Fine Art

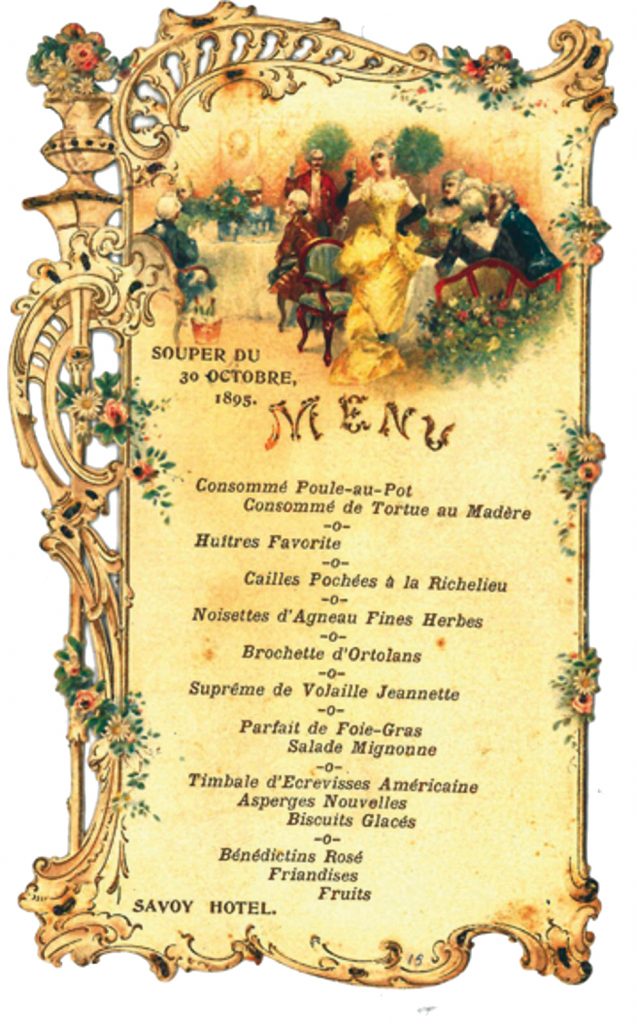

The meal concluded with fruit – small-scale peach, plum and cherry trees and grapevines were brought to the tabular array and the diners were given golden scissors to serve themselves. The cost for the ten guests was £15 per caput – a weekly salary for the upper-middle class. But the hosts of this spectacle of luxury were not royalty or aristocracy, but two Jewish businessmen – members of the nouveau riche, one of them in the fur trade – and the dinner was a sign of a rapidly changing social order every bit the end of the century approached. At the Savoy, Escoffier – a Frenchman in London – was role of the transformation not simply of gastronomy merely of British social club.

Escoffier, whose 175th anniversary year is beingness celebrated and whose touch on on London is reflected in the name of Gordon Ramsay's new French fine dining Eating place 1890 at The Savoy, was an unlikely revolutionary. Short of stature and quietly single-minded, his appearance belied the creative whirlwind within. Born in late 1846 the son of a blacksmith and raised in poor, rural Provence, his dreams of being an artist were rapidly stifled equally he was apprenticed, aged just xiii, to his uncle at his restaurant in Nice, which served the rich who wintered in the southward of France.

There Escoffier encountered something akin to Hell – a basement kitchen filled with fume, intense heat, heavy drinking and not-and then-latent violence. Information technology was a standard for eatery kitchens which he would become on to turn on its head, first resolving to immerse himself in his new career. "Having realised that in cooking in that location was a vast subject field and development, I said to myself, 'Although I had not originally intended to enter this profession, since I am in it, I will work in such a way that I will rise above the ordinary, and I will do my best to raise again the prestige of the chef de cuisine'," he later wrote.

A task at the bohemian Le Petit Moulin Rouge, near the Champs-Élysées, took Escoffier to Paris, and when the Franco-Prussian War broke out he was conscripted every bit an army chef, facing the ultimate catering challenge when he had to feed the ground forces of the Rhine headquarters through the 10-week siege of Metz. He developed an unlikely but urgently practical involvement in new canning and preserving techniques, which he would afterward pursue through founding a tinned-love apple business. Taken prisoner, he became chef to the captured head of the French regular army, Marshal MacMahon, and later escaped the siege of Paris past a whisker.

More a decade of building a reputation in both Paris and the s followed, and Escoffier was nearly 40 when he was headhunted to work at the Grand Hotel Monte Carlo by its dynamic manager, César Ritz. Ritz – an ex-waiter with a hyper-sensitive experience for proficient service, an aesthete'due south obsession with perfect decor, from the flowers to the lighting, and a talent for dramatically staged dining events – was determined to make the Yard one of the chicest places to be seen in Europe. His vision of the mod hotel was complemented past Escoffier's own revolutionary ideas.

Escoffier reorganised the Grand'south kitchen into an assembly-line system, inventing the modern kitchen brigade and perfecting the service à la russe arroyo, where dishes were cooked to order, replacing the banqueting

style of earlier in the century. Escoffier'due south system did away with the noise and chaos he had experienced as an apprentice, replacing it with a methodical calm that ensured dishes arrived in a timely, synchronised manner. Escoffier decreed that the cooks in his kitchen were to keep their whites clean and never article of clothing them on the street. Swearing, tobacco and alcohol were banned. His vision, in short, was one of the professionalisation of the trade.

It was too at the Grand that Escoffier proved he was a truthful culinary artist, designing dishes that were lighter, more refined and more focused on flavour and quality ingredients than the thoroughly over-the-top confections of Marie-Antoine Carême, who had set the standard of haute cuisine earlier in the century. There Escoffier too invented the prix fixe menu, offering diners a curated fine dining feel.

Merely his modernising impulse ("People who exercise non accept the new, abound sometime very quickly," he one time wrote) was always tempered by a delivery to those traditions worth keeping – the archetype sauces, cooking on wood and coke stoves instead of the new gas and electrical cookers, and using heavy iron and copper pans. In the summer flavor, the Ritz-Escoffier duo could be found working the same magic at the Grand Hôtel National in Lucerne.

Meanwhile, in London, The Savoy was not experiencing such success. Richard D'Oyly Menu had opened the establishment in 1889 with the vision of giving London its first truly luxury hotel, but while it had provoked plenty of initial interest, it before long began to lose money. Having stayed at the Monte Carlo Yard, D'Oyly Carte knew Ritz was the man to requite The Savoy the

indefinable magic that would bring customers back. Ritz, in turn, knew

his formula for success wouldn't work without Escoffier'due south food and persuaded the chef to join him in turning The Savoy's fortunes around.

To Escoffier, overseeing a eatery in London seemed a fool'due south errand. London had no public eating house civilization – the British upper course had ever dined in private, hosting events at their homes or eating at their sectional clubs – and the French chefs who had staffed its gentlemen'due south supper clubs had constitute the British palate to exist an unadventurous one.

In Monte Carlo and Lucerne Escoffier had served a stream of European sophisticates, merely in staid London he feared that he faced edifice a sense of sense of taste from the footing upwards.

Escoffier'southward welcome to The Savoy didn't bode well. The previous chef had trashed the kitchens and turned the food stocks out on to the floor to spoil on being sacked. Escoffier, ever the professional person, rallied his staff, apace restocked and got the lunchtime service out.

At The Savoy, Escoffier invented dishes that became legendary. He served frogs' legs set on a "pond" of champagne jelly with chervil and tarragon "in imitation of water-grasses" to the Prince of Wales, euphemistically calling them Cuisses de Nymphes à fifty'Aurore ("Nymph Thighs at Dawn"). In that location was the famous pêches Melba for Dame Nellie Melba, probably the about famous singer in the world at the time, peaches poached in vanilla syrup, served on vanilla water ice foam and topped with raspberry puree.

Dishes were especially designed for actresses Sarah Bernhardt (a strawberry dessert and a veal soup), Gabrielle Réjan and other historic figures. The actor Benoît-Abiding Coquelin, who later had a sole dish defended to him by Escoffier, told the chef that his nutrient had done nothing less than make dreary England "fit to live in", a thought that may have been on Escoffier's heed when he wrote, "So long every bit people do not know how to eat, they will non have whatsoever skilful cooks."

While Escoffier had already put The Savoy's kitchen brigade arrangement and style of dining into practice in Monte Carlo and Lucerne, London was a far superior stage. It was the biggest metropolis in the world, and The Savoy was a huge, ultra-modernistic hotel. It was the first fully electrified public building in the world. There was no more high-profile place to put his innovations on show. And, equally Luke Barr argued in Ritz and Escoffier: The Hotelier, the Chef, and the Ascent of the Leisure Class (2018), in London, Escoffier's food was a focus around which social mobility was increasing and the former hierarchies were challenged.

The Savoy created a new, democratic, glittering public sphere where to see and be seen was every bit much function of the pleasure of a repast as the food itself, and both women and the newly moneyed staked a claim to a public social identity. Modern restaurant dining equally we know information technology came to London for the first time under Escoffier'due south tenure. He was feted by the likes of early eatery critic Nathaniel Newnham-Davis, whose Gourmet'southward Guide to London swooned, "M. Escoffier, had he been a man of the pen and not a man of the spoon, would take been a poet."

But Escoffier was about to detect out that pride comes earlier a fall. Chefs taking kickbacks from suppliers was hardly unknown, but The Savoy'south

management was unamused to notice that their suppliers would routinely

evangelize orders to their kitchens brusk of produce to make up for their payments, in both cash and appurtenances, to Escoffier. Along with Ritz and maître d' Louis Echenard, accused of like wrongdoing, he was chosen into D'Oyly Menu's presence one March Mon in 1898 and summarily sacked. The

papers reported that his loyal band of cooks defiantly wielded their chef's

knives at the news and the police had to be chosen. Escoffier later admitted a

liability to The Savoy of a huge £eight,000. But the scandal did not tarnish the Ritz-Escoffier magic and their famous clients followed them to the Paris Ritz and afterward to both the Carlton and the Ritz in London. And it was only after The Savoy, and as he entered his 7th decade, that Escoffier began to anticipate today'south celebrity chefs by publishing a bestselling book.

Le Guide Culinaire, published in French republic in 1903 and appearing in English language in 1907 as A Guide to Mod Cookery – a piffling 2,973 recipes to the French edition's more than than 5,000 – set Escoffier's gastronomic innovations down in black and white, codifying the cadre techniques and becoming the bible of culinary excellence. It is still in print. Stock is everything in cooking – at least French cooking. Without it, nothing can be done.

Adjacent, Escoffier oversaw the cosmos of world-grade restaurants on the luxury sea liners of the Hamburg America Line and so went to America for the first time to set the kitchens at the Ritz-Carlton in New York.

The commencement world war brought a new age and robbed Escoffier of a son. The all-time years were over. He retired to his Monte Carlo estate in 1920, a year

after he had been awarded the Légion d'honneur. But he lived to run across both his

style of luxury embraced with wild enthusiasm in the 1920s, and Le Guide

Culinaire define fine food for the new century.

He died in 1935, aged 88. His creation of the modern kitchen and of dining equally public spectacle is still with us today, and while y'all are unlikely to encounter ortolans and turtle fins at your adjacent meal out, a little fleck of

Escoffier will still be part of your experience.

Source: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/auguste-escoffier-masterchef-the-original-professional/

0 Response to "One of the Things That August Escoffier Did to Back Up His Claim That High Cuisine Is a Fine Art"

Post a Comment